Hippocratic Oath

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Hippocratic Oath (disambiguation).

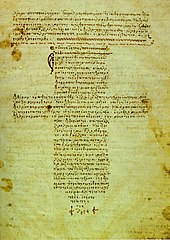

The Hippocratic Oath is an oath historically taken by physicians and other healthcare professionals swearing to practice medicine honestly. It is widely believed to have been written by Hippocrates, often regarded as the father of western medicine, or by one of his students.[1] The oath is written in Ionic Greek (late 5th century BC),[2] and is usually included in the Hippocratic Corpus. Classical scholar Ludwig Edelstein proposed that the oath was written by Pythagoreans, a theory that has been questioned because of the lack of evidence for a school of Pythagorean medicine.[3] Of historic and traditional value, the oath is considered a rite of passage for practitioners of medicine in many countries, although nowadays the modernized version of the text varies among them.

The Hippocratic Oath (horkos) is one of the most widely known of Greek medical texts. It requires a new physician to swear upon a number of healing gods that he will uphold a number of professional ethical standards.

Contents

[hide]Oath English Translation[edit]

English translation, version 1[edit]

Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant:

To hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him, and if he is in need of money to give him a share of mine, and to regard his offspring as equal to my brothers in male lineage and to teach them this art — if they desire to learn it — without fee and covenant; to give a share of precepts and oral instruction and all the other learning to my sons and to the sons of him who has instructed me and to pupils who have signed the covenant and have taken an oath according to the medical law, but to no one else.

I will apply dietetic measures for the benefit of the sick according to my ability and judgment; I will keep them from harm and injustice.

I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody if asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect. Similarly I will not give to a woman an abortive remedy. In purity and holiness I will guard my life and my art.

I will not use the knife, not even on sufferers from stone, but will withdraw in favor of such men as are engaged in this work.

Whatever houses I may visit, I will come for the benefit of the sick, remaining free of all intentional injustice, of all mischief and in particular of sexual relations with both female and male persons, be they free or slaves.

What I may see or hear in the course of the treatment or even outside of the treatment in regard to the life of men, which on no account one must spread abroad, I will keep to myself holding such things shameful to be spoken about.

If I fulfill this path and do not violate it, may it be granted to me to enjoy life and art, being honored with fame among all men for all time to come; if I transgress it and swear falsely, may the opposite of all this be my lot.[4]

English translation, version 2[edit]

I swear by Apollo, the healer, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panacea, and I take to witness all the gods, all the goddesses, to keep according to my ability and my judgment, the following Oath and agreement:

To consider dear to me, as my parents, him who taught me this art; to live in common with him and, if necessary, to share my goods with him; To look upon his children as my own brothers, to teach them this art; and that by my teaching, I will impart a knowledge of this art to my own sons, and to my teacher's sons, and to disciples bound by an indenture and oath according to the medical laws, and no others.

I will prescribe regimens for the good of my patients according to my ability and my judgment and never do harm to anyone.

I will give no deadly medicine to any one if asked, nor suggest any such counsel; and similarly I will not give a woman a pessary to cause an abortion.

But I will preserve the purity of my life and my arts.

I will not cut for stone, even for patients in whom the disease is manifest; I will leave this operation to be performed by practitioners, specialists in this art.

In every house where I come I will enter only for the good of my patients, keeping myself far from all intentional ill-doing and all seduction and especially from the pleasures of love with women or men, be they free or slaves.

All that may come to my knowledge in the exercise of my profession or in daily commerce with men, which ought not to be spread abroad, I will keep secret and will never reveal.

If I keep this oath faithfully, may I enjoy my life and practise my art, respected by all humanity and in all times; but if I swerve from it or violate it, may the reverse be my life.

Modern use and relevance[edit]

The oath has been modified multiple times. One of the most significant revisions was first drafted in 1948 by the World Medical Association. Called theDeclaration of Geneva, it was "intended to be a self-conscious rewriting of the Hippocratic Oath, reaffirming Hippocratism in the face of the shame and tragedy of the German medical experience". The Third Reich had deemed that there was such thing as a life not worth living, and this was seen in their medical experimentation on Jews throughout WWII.

In the 1960s, the Hippocratic Oath was changed to "utmost respect for human life from its beginning", making it a more secular concept, not to be taken in the presence of God or any gods, but before only man.

While there is currently no legal obligation for medical students to swear an oath upon graduating, 98% of American medical students swear some form of oath, while only 50% of British medical students do. [6] In a 1989 survey of 126 US medical schools, only three reported usage of the original oath, while thirty-three used the Declaration of Geneva, sixty-seven used a modified Hippocratic Oath, four used the Oath of Maimonides, one used a covenant, eight used another oath, one used an unknown oath, and two did not use any kind of oath. Seven medical schools did not reply to the survey. In France, it is common for new medical graduates to sign a written oath.[7][8]

In the United States, the majority of osteopathic medical schools use the Osteopathic Oath as well as the Hippocratic Oath. The Osteopathic Oath was first used in 1938, and the current version has been in use since 1954.

In 1995, Sir Joseph Rotblat, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize, suggested a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.

See also[edit]

- Declaration of Geneva

- Declaration of Helsinki

- Hippocrates

- Hospital Corpsman Pledge

- Human experimentation in the United States

- Medical ethics

- Nightingale Pledge

- Nuremberg code

- Oath of Asaph

- Oath of the Hindu physician

- Osteopathic Oath

- Physician's Oath

- Primum non nocere

- Seventeen Rules of Enjuin

- Sun Simiao

- White Coat Ceremony

References[edit]

- ^ Farnell, Lewis R. (2004-06-30). "Chapter 10". Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 234–279. ISBN 978-1-4179-2134-8. p.269: "The famous Hippocratean oath may not be an authentic deliverance of the great master, but is an ancient formula current in his school."

- ^ The Hippocratic oath: text, translation and interpretation By Ludwig Edelstein Page 56 ISBN 978-0-8018-0184-6 (1943)

- ^ Temkin, Owsei (2001-12-06). "On Second Thought". "On Second Thought" and Other Essays in the History of Medicine and Science. Johns Hopkins University. ISBN 978-0-8018-6774-3.

- ^ The Hippocratic Oath: Text. Translation. and Interpretation. by Ludwig Edelstein, Supplements to the Bulletin of the History of Medicine. no. 1943).

- ^ National Library of Medicine 2006

- ^ Dorman, J. (September 1995). "The Hippocratic Oath". Journal of American College Health 44 (2): 84-88. ISSN 0744-8481. Retrieved 9-20-2013.

- ^ Sritharan, Kaji; Georgina Russell, Zoe Fritz, Davina Wong, Matthew Rollin, Jake Dunning, Bruce Wayne, Philip Morgan, Catherine Sheehan (December 2000). "Medical oaths and declarations". BMJ323 (7327): 1440–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7327.1440. PMC 1121898. PMID 11751345.

- ^ Crawshaw, R; Pennington, T H; Pennington, C I; Reiss, H; Loudon, I (October 1994). "Letters". BMJ 309 (6959): 952. doi:10.1136/bmj.309.6959.952. PMC 2541124. PMID 7950672.

- Notes

- The Hippocratic Oath – an article by The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- The Hippocratic Oath Today: Meaningless Relic or Invaluable Moral Guide? – a PBS NOVA online discussion with responses from doctors as well as 2 versions of the oath. pbs.org

- Lewis Richard Farnell, Greek Hero Cults and Ideas of Immortality, 1921.

- "Codes of Ethics: Some History" by Robert Baker, Union College in Perspectives on the Professions, Vol. 19, No. 1, Fall 1999, ethics.iit.edu

External links[edit]

- Hippocratic Oath, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (h2g2).

- Hippocratic Oath – Classical version, pbs.org

- Hippocratic Oath – Modern version, pbs.org

- Hippocratis jusiurandum – Image of a 1595 copy of the Hippocratic oath with side-by-side original Greek and Latin translation, bium.univ-paris5.fr

- Hippocrates | The Oath – National Institutes of Health page about the Hippocratic oath, nlm.nih.gov

- Tishchenko P. D. Resurrection of the Hippocratic Oath in Russia, zpu-journal.ru

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment